Be With: Hi Ned, apologies for the previous aborted attempts at contacting you…

Ned Doheny: Oh no problem! We’re all victims of technology. So how are you doing today?

BW: We’re good Ned, thanks. More pertinently, how are you?

ND: Well I just got up, it’s early here. I’m going to see a James Brown movie with a British friend of mine tonight. It’s 68 degrees temperature-wise and there’s not a cloud in the sky.

BW: And where are you based these days?

ND: I’m living on my family ranch in Ventura County - it’s quite large and lovely. I was just walking through the tennis courts and I saw some bear tracks. Now, I know they were bear tracks as I saw the actual bear a month and half ago! I was armed with nothing but a walking stick and a dry sense of humour. That got me through it. That and a brown pair of slacks will get you a long way around here.

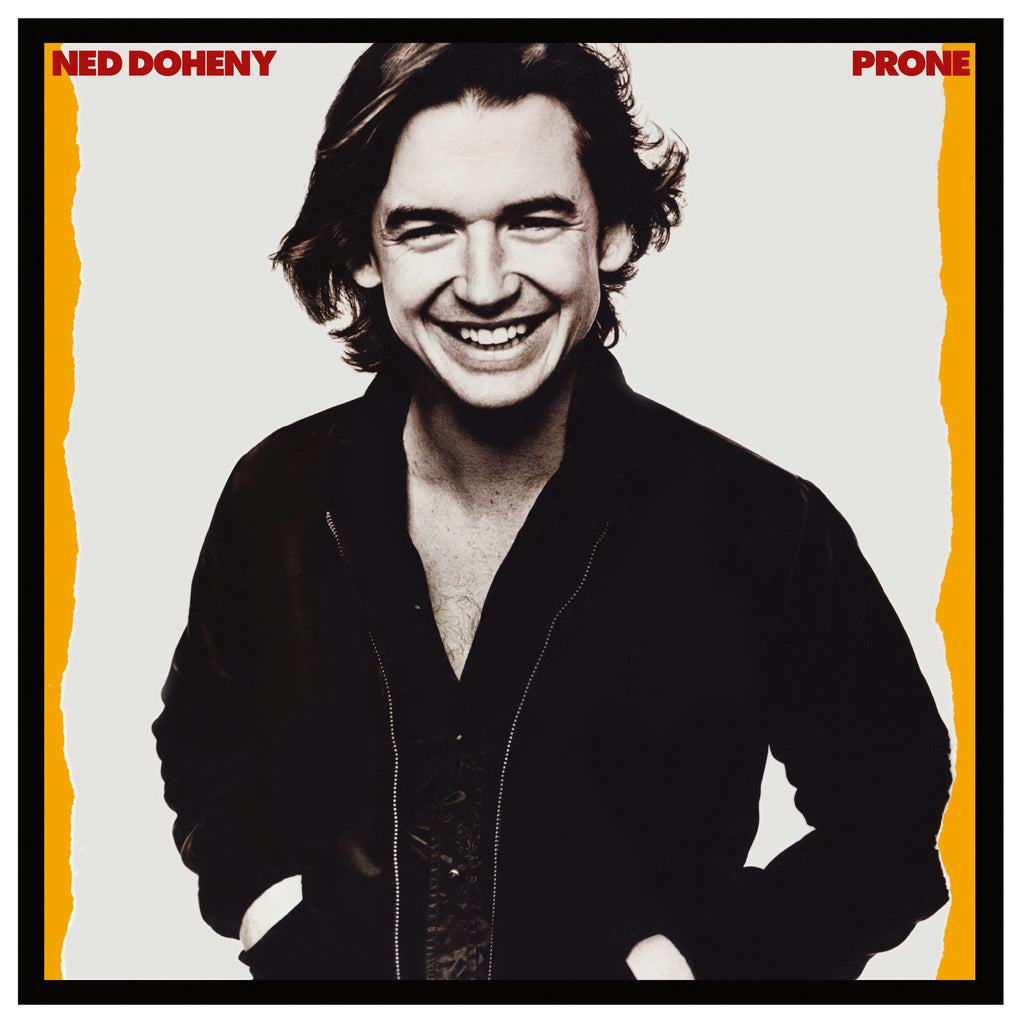

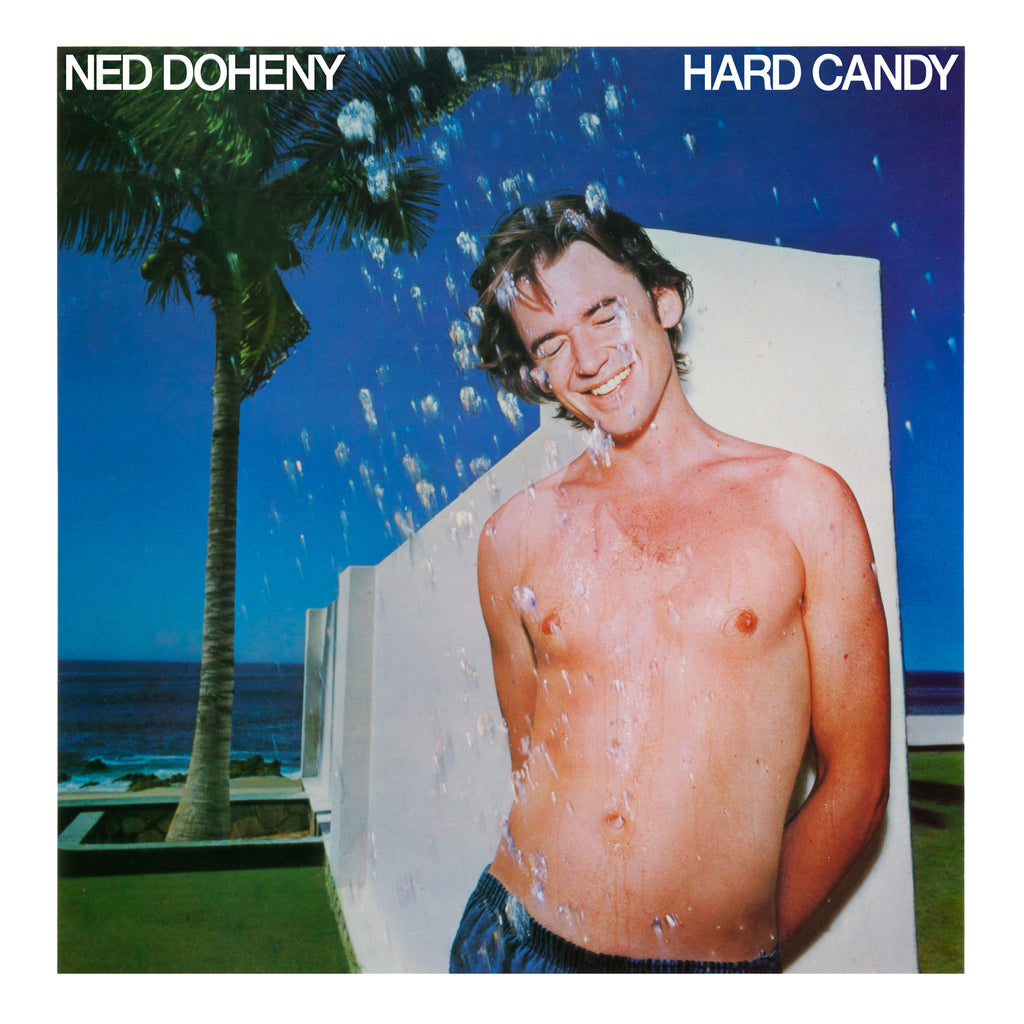

BW: No doubt! So, Be With have officially licensed your classic Hard Candy and Prone LPs as part of our reissue series. What are your recollections of those particular records?

ND: Well, we’re talking about recordings that were 35-40 years ago. But let’s see. My first album for Asylum - which a lot of people also want to see reissued… I’m told – was very personal. They always are because they represent your first real statement. And, ultimately, you’ve had time to chew on the tunes to get them to a certain level of… righteousness.

But, after that record, I moved to a more corporately guided record company. Now, I didn’t exactly make concessions per se but I wanted to make something a little bit more… how do I put this… commercial. Or, more focused in terms of the era that I found myself in. Because we had really high hopes for that first album but it didn’t pan out. It wasn’t a conscious shift, just a point of evolution I guess.

The recordings happened at Clover Studios, owned by Steve Cropper, in LA. And the usual battery of suspects were there. Everything came together quickly. The tunes were already done so it all went smooth. We didn’t spend a ton of money… it was quite easy. We didn’t trouble over anything and I didn’t have to come up with a chord change or spend hours over the lyrics.

BW: And were they pleasurable experiences?

ND: Oh yes. Always. The process of writing and recording - I’m crazy about it. I know it’s difficult for some people. And if there’s nobody there, I’ll do it all by myself. I enjoy the process of refining something and making it accessible. If you can knock yourself out first then you can hope that peoples’ taste will converge with yours eventually and they’ll figure out what you’re doing. It may take 40 years!

BW: And were you concerned with how they were going to be received at the time?

ND: You never have any idea of how they’re going to be received. It’s taken so long to find this… ‘resurgence’, if you like. I find it baffling. And, apparently, a lot of people arrived at this at the same time which is a wonderful thing. It’s not just Be With.

BW: It’s a global thing…

ND: I certainly hope so. It’s turning up in all sorts of places now and I’m scratching my head a little bit. But, everything has its own time. How great is that? To have found another generation. How great is that?! I can’t complain about that.

Also, to have lived in the middle of a certain zeitgeist, a certain perspective, it’s hard to remember it now. It was so creative and fraught with opportunity. People were taking risks and being extremely naughty and all the rest of it. It was a very different time to what it is now. So perhaps that appeals to new listeners, too.

You know, you don’t know it at the time though. That things won’t always be around, I mean. Certain styles of music, like jazz, for example. Even the air around has changed. There’s a hunger to recapture that period – look at the compilations and the biographies etc. - among people who weren’t part of that. They want to figure out what that period was all about. To me, it’s kind of depressing. Take the Kalashnikovs and go home. The war is over. Go home. Hopefully they’ll be another resurgence of creativity in spite of what’s happening in music at the moment and the world at the moment. The times are not as hopeful as they were when we were prancing around with long hair taking too much of everything.

BW: What was so unique about the spirit of that period?

ND: Well you know those heart-warming pet videos you see on Facebook? Like the one in which young eagles are falling over when it’s their very first time out the cage? Well, my generation was a bit like that. Because the generation ahead of us paid heavy.

Heavy, heavy, hea-vy.

Your grandparents would have lived through bombs whistling over their head. They faced a seething force that was truly evil in intent. So, what happened in the early 60s was very staid and conservative. It was like the World War Two club; ‘Yeah this is how we are gonna fucking do it and that’s that.’ So, it was all skinny ties, small lapels, short hair, college as a fast track to some sort of significant job, get married, have kids. It was all pretty tightly wrapped. In terms of fashions and attitudes.

We were like the Samurai who has no master. No projection of a feudal family. So, when all these outrageous pop things were happening in that era, it was a reaction to World War Two. We were escaping our era, trying to make money and survive. People began to experiment for themselves. We were a lot like those eagles. People got out of their cages - imaginary or otherwise – and realised that, hey, you don’t have to cut our hair. You can do or take dangerous things and you won’t die. It spawned a whole, incredible shift of consciousness.

But it didn’t pan out too well did it? The world couldn’t be saved. Look at the realities of today - the romantic fantasy is exactly that.

BW: Why are the young of today not able to recapture that spirit of experimentation which your peers enjoyed?

ND: I mean, these days, my son can grow his hair long, dye it purple and I’ll just shrug and look at him and say, ‘ok!’

My father would knock me out! When my hair was just barely caressing the tops of my ears I couldn’t come in the house. I wasn’t allowed for thanksgiving! So, in that period, there was something to rebel against.

Now we’re all just drifting in a sea of mediocrity and disproportionate amounts of money relative to talent. I mean, Jay-Z and Beyoncé - do you really think people will be sat around listening to that in the future? Maybe they will, but I don’t think they will in the same way people listen to Miles Davis or The Beatles. It’s all put together to make money. There’s not much thought behind it. Although I’m sure that would be the first thing that the Eagles would say if they were asked how they designed their music.

But, ultimately, I guess there’s no resistance. Nothing to push off from or rebel against. We did everything. So now, all that’s left is to either kill yourself or become an accountant.

BW: So what was it about music initially for you? That spark in terms of the musicians etc. Was it that Elvis moment?

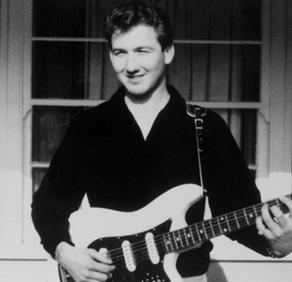

ND: At the very, very, very, very beginning, it was something that I did that defined me in a way that made my family extremely uneasy; even though, in a way, they aided and abetted me. Although I’m sure they came to regret it. Music became mine in a way. I didn’t know anyone else that played guitar. So, whenever I heard the word ‘guitar’, I thought, ‘that’s mine – that’s my instrument’. In terms of the spark, it was a succession of people that had gone a lot further than I. There was a beautiful instrumental that I used to listen to on rock radio at night by Santo and Johnny. James Burton doing incredible guitar work for Ricky Nelson. God, I loved James Burton - what a roaring talent he was. I used to watch Ricky Nelson on television and think ‘yeah, that’s me! There’s still time, we can do this’.

I was probably around nine. So, he was older than me and a great looking kid and the songs were great. And then one thing led to another and I’m thinking ‘holy shit, can I really do this? Can I just go from place to place playing and doing this?’ Then, of course, your countrymen sort of sealed the deal on that. We all sat in movie theatres and watched men being chased by women. That was pretty simple for us. I don’t think there’s a single person I know who didn’t see that and wasn’t changed by it. Virtually everyone I knew. And my background was not really folk - that stuff was a little prosaic for me - but I’d played for long enough that I just started to get better. By the time The Beatles came along, I’d already been playing for 8-9 years so I was already… good.

BW: And did the British invasion make sense to you? Did it seem like another path you can go down?

ND: Well, yeah, sure. You’ve got a fidgety generation who can’t really find any correspondence with much of that doggy in the window or Please Mr. Custer or any of the novelty tunes. Even though they’re kind of fun to listen to now, it wasn’t anything that really spoke to us.

And, all of a sudden, you’ve got a bunch of guys where the operative word would be fearless. Not only were they extraordinarily good at what they did and had put in tremendous amounts of time to play live music on a level that is still shocking, if you go back and listen to it.

You see a bunch of guys with long hair and you think ‘you know what, I’ve spent my whole life having my haircuts inspected by my parents!’ I mean, my god, it was like the doors had been flung open wide and we were let out! We escaped. So, the timing was beautiful as it was right around the time I was leaving high school and then I was off to college, I hitchhiked to the first Monterey Pop Festival, I did my first session when I was 17-18 and at that point it really became sort of a juggernaut. That was before the whole thing had been subsumed by the entertainment industry. For me, the Monkees were really the end of everything. I mean, I think they were basically a bunch of harmless children but for all of us it sort of meant it had now been taken out of our hands and formally recognized by the very people who we were asking to kiss our collective asses! Hahaha. So, I guess, at that point we were kind of done. And then after that it was sort of scuffling around looking to make the next buck. And you’re only as good as your next tune.

BW: Did the band thing never appeal to you? Or did you always know that you’d go down the solo singer-songwriter route?

ND: Well, I love playing with bands. To play in a really great band where you start exploring, where you really have a real affinity for one another and a sense for one another… I mean, certainly I would have to say there are good examples of the music the Beatles did as solo artists but I don’t think anything they did as solo artists can touch what they did as a collective. I think even they were kind of shocked by what they were capable of. Even with Lennon dead and them resuscitating that song – what was it, ‘Free As A Bird’? I remember sitting at my friend’s house in front of these huge speakers and listening to it and going ‘My god… it sounds exactly the same and one of them isn’t even there!’

I wrote to Hamish (Stuart, of Average White Band) and told him I’m coming to Britain to play and I said they want me to come and play by myself and I said ‘Fearless me’ and he said he couldn’t do it. He has to have a band. But, there’s a process with a band of sharing the vision and supporting it and the energy from that stuff is, god, just crazy. Get a whole room full of people that worked up? Pretty outstanding.

But, you know, I was friends with Jackson (Browne) and we hung around a lot in our teens and he was a very, very deliberate and methodical songwriter and I think he really let a lot of us understand how much work was involved in getting it right. You know, poets are notorious. And I‘m not calling Jackson a poet as that’s another term I don’t toss about. But poets as a group will agonize over a particular word for years and they’ll be in some sort of writing hell. And that’s really what you’ve got to do if you want it all to behave the way you want it to. I learned that from them – that’s what intrigued me and off I went in that solo direction.

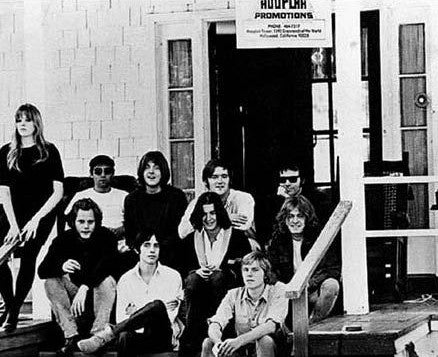

BW: You fell in with the Paxton Lodge crowd – if you can call it that – and I suppose that was before Jackson really made it big. What was happening with those guys?

ND: Well, Jackson was doing quite well in clubs and had his ‘me playing by myself shit’ down pretty cold and he had enjoyed some success with the folk community - more than any other - and I knew very little about him. But, I answered an ad in a paper. They said they were looking for a guitarist so I trotted up to this hotel room on the Sunset Strip with my guitar and my tiny amplifier and played and then was promptly asked to come up to the Laurel Canyon house where Jackson Browne would be.

And I thought he was going to be an enormous African American - which sounded great to me - but he turned out to be a sort of funny Mexican looking kid. I just played along with him as that’s how I’d learned to do it. And we jammed a lot in those days; a word I hate, by the way. Played together a lot might be better. Yeah, so, that was my first experience with him and then I got drawn into that particular group and there was a lot of naughtiness and celebrities – people I’d never met before.

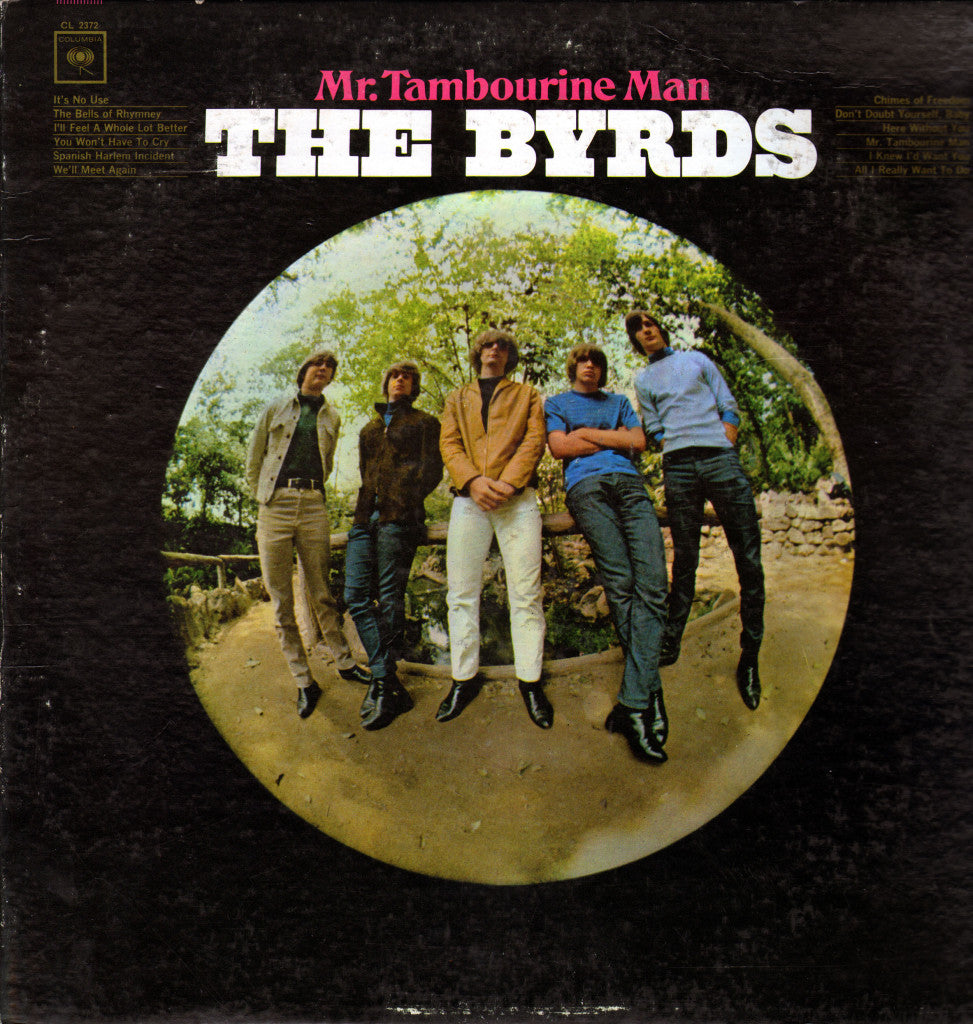

I met David Crosby – I couldn’t believe it. I mean, that first Byrds record, I thought it was the greatest thing ever.

I met Nico – she of Velvet Underground fame - when she had hearing. I mean, no better way to be thought of as an enigma than by not being able to hear people. So you could very easily go ‘So, how do you like Los Angeles’ and you’d get, by way of response, ‘Brian Jones sleeps with dead people.’ So, she was a confusing entity but, yeah, I got to meet and play with the Incredible String Band and Lonnie Mack – one of my great heroes - who had throttled a Chuck Berry tune and tore to pieces. So that was really kind of it. When Bobby Kennedy died, we were all sitting in front of the television set that day in that house and I think at that point I passed under the velvet rope.

BW: Was the Paxton Lodge a sort of metaphor for the hippie dream dying or is that placing too much importance on it?

ND: Well, I can’t speak too much to the hippie dream but I can say that at Paxton Lodge we basically… You know utopia and dystopia are separated by a membrane no thicker than the skin of an onion? Well, it started out as utopia. Which was a bunch of guys up there in the natural world making music together, free from the constraints of urban living - that was how Barry Friedman sold it to Jac Holzman anyway. But when it came down to it, Barry Friedman was shooting heroin and people were smoking weed before they got out of bed in the morning and, you know, the band were sort of… there wasn’t a kind of focus. And the place was so seductive. You were eating these beautiful meals and surrounded by nature and ‘wow it’s just the greatest thing ever.’

But, in terms of imagining that we would be as fortunate as those we saw in the darkened movie theatre...When that dream collapsed, everyone scurried for cover. A lot of people never made it back. I chose to study classical guitar for a year to bring some economy to the work I was doing. I wanted to make sure my little finger was not being left out of the equation. So, the idea of being able to float into wonderfulness – that part of the dream died. And we realised at that point that the competition was stiff. And there were some really, really great people making it look easy.

BW: And that’s when the singer-songwriters came out, after that…

ND: Yeah, yeah. I mean, obviously Dylan was sort of the Colossus of Rhodes on that one and we all kind of scurried between his ankles in that particular chapter. James Taylor made it a little more romantic in a mundane, welcoming way and we all followed suit. I’m much more comfortable with the spoken word than the written word so it was a reach for me. So, my singer-songwriting business was the by-product of an act of will, essentially. And that was it really.

BW: Were you tight friends with Jackson yet? Had you come across the Eagles at this point?

ND: We were all good friends. I can’t honestly say I was really good friends with Don (Henley) and Glenn (Frey). I mean, we were friends. In fact, I originally played Get It Up For Love for Glenn and that was before any lyrics were finished and he was really keen on finishing that one with me. I mean, economically, it would have been a lot more fascinating than what it turned out to be… but I don’t think it would’ve been as good a song.

The most brotherly to me was Jackson. And we still are good friends. He wrote 3 very nice paragraphs about me that appeared in Rolling Stone recently. We never betrayed one another. It wasn’t cut throat and competitive like it could be with the others.

It could be really aggressive, at times. Some people I cared for and thought were immense talents but I never wanted to own any of their albums. They were extremely good for representing their era, people like Joni (Mitchell) or the Eagles.

BW: Did they have more drive than you?

ND: Yes absolutely true. There was a tremendous amount of ambition within the groups. I had a fall-back. My great-grandfather (Edward L. Doheny) was a celebrity in the world he came from. By contrast, these musicians came from relatively poor backgrounds to come to LA to strike it rich. I could afford to be unsympathetic when people wouldn’t keep their word or meet me elsewhere. It was like ‘fuck you’. I could take my football home with me.

BW: When people first got that taste of all the sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, did they lose something of themselves?

ND: It’s a little bit Faustian. There was a great article from your country recently where it was found that those with a proclivity for comedy had tendencies towards mental illness. They see the opposite, filthy aspects of any situation. The irony of celebrity is that many people imagine that if you have more money and you become better looking or you have success it will somehow heal the wounds that made them start that process in the first place. You then become objectified by anyone and everyone. Any attractive woman will tell you what it feels like to be objectified. It’s a lonely composition. It puts more distance between those and everyone else. You’d just get stared at in a restaurant on your own as if you’re a large grasshopper or something.

Through my family history, I had knowledge that success and power isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be. People think you have something that they want and they either get angry or covetous. They think you must have broken the rules somehow to get ahead. Or think, ‘why should you have it and why not me?’ And now, real enmity exists between the classes more than ever in my country and, of course, the current rich have really done a lot to exploit that. They’ve pitted people against each other rather than working together.

But yeah, my Great Grandfather was splashed through the headlines and he lost his only son and he was a tough guy who’d gone through the jungles of Yucatan with a sidearm at the turn of the century searching for oil. It takes a lot to break somebody like that. When first staying in his house he slept on the floor as he was uncomfortable sleeping with a roof over his head. He felt trapped inside by something.

But when he died, the consensus is that he was broken. His heart was broken. He lost his only son and felt the full measure of humanity of his time. It broke him. So yeah, it’s pretty horrendous what can happen if people have the perception that you have advantages that you have acquired improperly or, in some ways, aren’t considered common.

But my Great Grandfather took every risk! He was lucky. I don’t believe he was an evil man. Strong, yes. He was a poor kid from Ireland and he climbed the ladder. So yeah, I do have that feeling about being able to return to my family and be with people who understand our situation.

BW: Did people act differently around you?

ND: Yeah. But when we were all pups, at the beginning, I didn’t feel like anyone had an axe to grind or anything like that.

But, you know, I was a good looking kid and I played guitar really well and I came from this family so I didn’t really fit into the model that was necessarily working on Asylum Records.

Plus, as time passed and I became a better guitar player, I tried to bring the songwriting sensibilities that were competing with the boys on Asylum into a larger rhythm context; that made me very different from them. My groove relationship - or my relationship to the groove in general - set me very much apart from them and, strangely, is the impetus behind the fact that people still listen to Hard Candy and Prone.

BW: Do you think you got off lightly then? In the sense that you didn’t achieve the fame of others in the circle? Joni, Eagles etc.

ND: Well, not really because we were all pretty relentless when it came to ourselves. There were a lot of opportunities I missed. If I’d even had a whiff of what the future was gonna be like I think I might have been a little bit more...focused. Focused on where I was gonna go and what I was gonna do. But life’s like that.

By definition, if you’re talking about a system where the punch line is that you have to give everything back - including your body - then the darkness will find everyone. Look at Robin Williams. A bright, funny, sometimes annoying but extraordinarily talented and much-loved individual whose only coping mechanism was to make it stop. So, everybody gets it and I was no exception. Things happened to me at the end of my twenties that caused parts of me to disappear. And, by that, I mean there was a certain Boy Scout-like feeling that if I did this and that then this would happen. And I lost my innocence. A chunk of me got remixed. Dylan put it really well in his line ‘you took a part of me that I really miss’ and I was no exception.

BW: So did you feel that you were treated badly by people like David Geffen then in that respect?

ND: Well, you know, as far as I’m concerned, I think Geffen in those days was kind of a legal criminal. We went over my publishing some years later and found that I’d been double charged for some things, all kinds of stuff really. That is not a wholesome human. Yes, we were ambitious; he was twelve times more ambitious as we were. And willing to sell us lock, stock and barrel to the highest bidder. And crush us if we resisted. I think he had his heart broken by Laura Nyro and thought, after that, ‘you know what? Fuck this.’

He was a gay man and being gay was not looked upon as charitably as it is these days so he had to struggle with that as well. But yeah, I think he looked at me and just had no idea what it was. I think on one level he probably saw me as an attractive kid but, on another level, he didn’t have a clue.

BW: And is the oft-quoted sauna story (that Geffen proclaimed to the naked men gathered in his hot tub – Jackson Browne, Don Henley, Glenn Frey and Ned Doheny - that his label would never be bigger than the people gathered there) true?

ND: It is certainly largely true. We were sold Asylum Records as a haven. The word ‘asylum’ obviously has several meanings, which I think is beautiful, and, as a song-writer, the double entendre is one of the great things you can obviously have or create. But I think David told us what he was obliged to tell us and then, as things changed for him, there were things he was obliged not to tell us. But, yeah, I think it was largely true and, with Asylum Records, we thought ‘oh great we’re with an enlightened record company’ which, in the fullness of time, became a contradiction in terms.

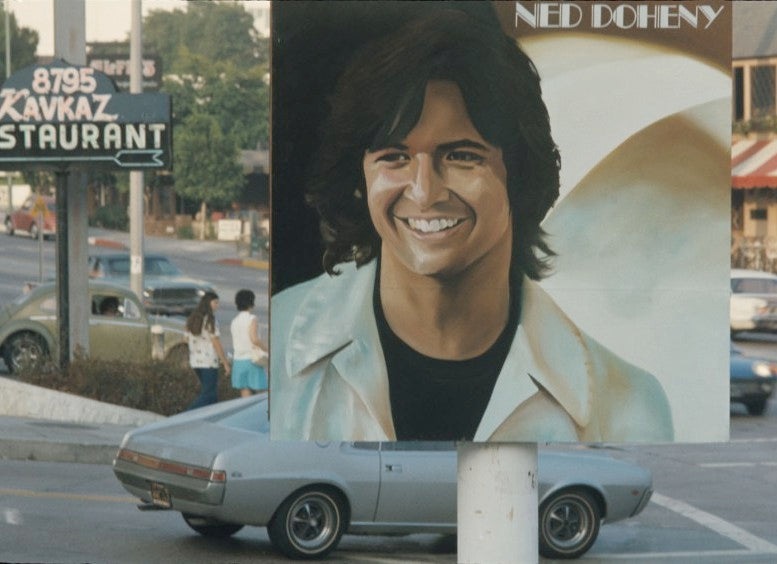

BW: And with the billboard promoting your debut LP, did you think success was just around the corner at this point?

ND: My billboard was actually pretty crappy – not even an actual billboard. It looked like the corner of a billboard. It had this quality of… it looked like I’d been dropped from a great height and then left in the sun. It was like a bunch of high school kids had been competing to do the Ned Doheny LP cover for Sunset Boulevard. I didn’t even look like myself and it was tiny and, at the time, David had spent a ton of money on Jackson who was really his chosen entity among all those people and I had to end up coming up with $25,000 to finish my own album. Which I had but, on the other hand, $25,000 in 1973 was a lot of money. It’s still a lot of money. But, in those days, it was a lot of money. And, at that point, I just thought… all right. Fuck you. You know? Fuck you and the horse you rode in on you little creep.

If I’d have done everything they said - which involved just putting me on the road endlessly until I become case-hardened - I‘m sure I probably would have been much more well known than I am now. But, for me, I looked at David and remembered all the things that were promised and thought ‘No. I will not go any further with you.’ And he always said you can leave whenever you want and a contract is just a handshake and when I tried to actually leave all of that stuff he said ‘You can’t do this you son of a bitch’ but there it was. It was a lie and some people benefitted from it. Some more than others. Me? Not so much.

BW: Do you think were you as easy a sell as the others? With your soulful and groove edge? Maybe you were harder for the marketing people at the time to package?

ND: Well, Joni thought I might break out and take advantage of what was becoming a more rhythm-orientated music at the time but, yeah, I think I was always a little strange. Plus, I grew up with conservative people and, by that, I mean people with a conservative impression about how people should live and survive and all the rest of that. So I always had a bit of a war going on between the wild knucklehead who wanted to scamper naked through fields and the guy who worried about how he was going to pay his taxes. So yeah, I think in terms of the Asylum situation – and you can see it in the photographs of us all together – I was just from another planet. Even when I made it to CBS records, I was put in a category with Boz Scaggs and Walter Egan. And Hard Candy died the death of a thousand cuts on that altar. And Boz made that wonderful record. That literally perfect record. ‘Lowdown’ was certainly a perfect record and that was that. They couldn’t put me on the shelf with the frozen foods and… what is that… the baked goods. Hard Candy was basically the end of it.

BW: It seems a lot more acceptable to be into so many different types of music now – in the 70s did people maybe find it hard to get a grasp on you and all your different elements?

ND: Well I think between all of the record companies, whether it was Asylum or CBS, I was probably my own worst enemy. I had a certain arrogance borne of profound concern. Who knows what would have happened if I’d been helpful? I mean, I thought Hard Candy was me being helpful.

Between the first one and Hard Candy, I made some adjustments that were extremely helpful and made me a lot more accessible. But I was speaking to a British guy in an interview the other day and he said ‘my wife and I played your first album at our wedding and we just couldn’t ever understand why you weren’t spoken of in the same breath as James Taylor and all those people’.

So, in answer to your question, I think… if the public has the chance to hear something, they’ll make their own decision and I will always trust them. I’ve never been in front of an audience that want you to fail. Individuals make up their mind about what they like. One of the things about my mini renaissance - or whatever you wanna call it - is that all the things that were put in place so long ago apparently still resonate with people. So I would have to feel that, if they’d been a bit more interest, a bit more money or if there hadn’t been Boz Scaggs or if I had gone on the road more (at CBS – a LOT more) or been more helpful, if there had been some way for a larger group of people to hear what I was doing, I think we would be talking about it all slightly differently.

BW: Do you look back fondly on Hard Candy and Prone?

ND: Oh yeah, I think I did a good job. There are words and things I don’t like but, yeah, by and large I was quite pleased with them. I think the people I did the first album with actually thought we might be famous because of what we were listening to in the studio. But yeah, for their time and where I was at, at those times, I thought they constituted nice pieces of work. There were some really good tunes on both those records.

BW: About this second coming – do you have any regrets from the first time around regarding not being more successful or is it more ‘that’s the life that’s chosen me’?

ND: I think we all have a destiny. In my great grandfather’s case it was inordinate success followed by a broken heart. Other peoples’ might be to only live four or five years in this life. The path I’ve been on has been extraordinarily fascinating. I have a book full of experiences that I wouldn’t trade for anything. Both my private and public life. Yeah, if I were to be taken now – I have lived well and honestly.

BW: Will we be reading that book anytime soon?

ND: Well the stories are there. My hope is… the very interesting thing is that the third LP (Prone) seemed to connect me to the DJ community in ways that none of us could have foreseen, certainly not CBS at the time. And a lot of the people that were there controlling the lives of people around them are now dead. So, you know, if some DJ still wants to knock out ‘To Prove My Love’ – that… how great is that?!

There’s nothing I would like better than to have a large enough audience to put a full band together and go out and perform. But, failing that, I am quite happy to go out by myself and there are a lot of stories to tell. Lots. Too many. And I will be paid for in board and slosh.

BW: What are you up to these days? Still writing and recording?

ND: Well, I finished The Darkness Beyond The Fire LP a few years ago and it was a distillation of a bunch of songs that I had written in Japan around the time of my divorce and I curled up in my studio at home and recorded it over the course of 4 years. I’d be sitting there with a little candle going and there’d be this music coming out of these great speakers and it would remind me of really just how much fun it was, in that time, and how wonderful it was to create things with your friends and have your bond deepened with them because of that. And I think it’s a great record – I would put it alongside anything I have done.

I now have so much material to perform that I didn’t have when I performed the first LP. I can pick and choose and do stories and all that. If I can somehow galvanize an audience when I play dates – and I don’t have illusions about how big that audience may be – but if I can just get a small but fierce band of supporters into what I am going to do next, then that would create what I would consider the fifth album. And, yeah, we’ve got lots of bits and pieces and things.

It’s a little bit more difficult to talk about ‘I want it, I had it, I lost it’ - which is most of the subject matter of our music. I mean, with the world browning at the edge, it’s kind of hard to talk about… pussy. In any of its incarnations. But yeah, I think it would be great to take a few more people with me (laughs uproariously) That sounds ominous! But there’s a lot of music there and there’s a lot to listen to and I think it’s even more rare than it was at the time…

BW: Were you pleasantly surprised when Be With licensed Hard Candy and Prone or were you aware of when DJs played your songs out regularly?

ND: Yes, kind of, in a weird way. There was a guy playing in a band called the Fabulous Handclaps, I think (The Phenomenal Handclap Band) His name is Daniel Collás. He was very interested in meeting me and so I did. Then I got a call from Scotty Coats who works for Innovative Leisure. And he wanted me to come and play in Palm Springs. There were a group of Ned Doheny fans who got really drunk one night and emailed me… and I answered them. Which shocked him no end and at that particular event I met a bunch of DJs who said how much they’d been influenced by my stuff and then I heard of the interest from Be With Records so things have been bubbling up on both coasts spontaneously and simultaneously.

My wife has kind of a mystical bent - if you will - and she holds such things to be self-evident. So she was like ‘well you know it was only a matter of time.’ She’s a Japanese national and Japan was very supportive of me at a time when support was precious.

And, strangely enough, if it all comes together for the Be With Ned tour, I’ll have a chance to play in Britain and Europe in March.

I suspect - I hope - that I’ll find something similar. It would be great fun. I’m so… curious to see what remains of my efforts on the European continent, also. In Great Britain, I’ve heard rumours. I’m curious to see. I will bring a needle and thread just in case things don’t go well.

BW: Hahaha. Excellent, you should. Ned - thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us - have a lovely day and weekend!

ND: And you too. It’ll be great to catch up again when I come over. We’ll hoist a few and talk treason.

You can of course order a copy of Hard Candy, Prone or Ned’s self-titled LP on lovingly packaged 180gram vinyl, officially licensed and on Be With Records.

You can also buy high quality prints of Pete Fowler’s wonderful Be With Ned tour posters - in very limited quantities. You can watch Pete talking through his process for creating the posters in this video over on Youtube.